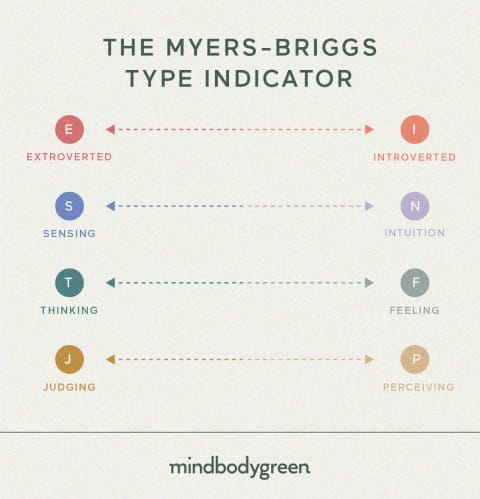

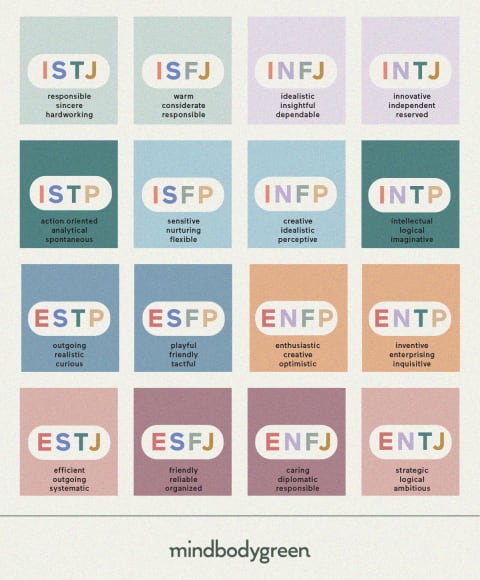

Here’s what to know about the MBTI, what research and personality experts think about the test, and how you can work with your results. According to John Hackston, the head of thought leadership at The Myers-Briggs Company, it’s important to note that while the MBTI is often called a test, there are no right or wrong answers, with each type having its own strengths and weaknesses. So, “test” really isn’t an accurate word. “The MBTI isn’t just a test or assessment. It’s a process,” he tells mbg. “So we don’t say, ‘Here are the results, good luck.’ We say, ‘Here are the results; now let’s talk that through to help make the results more relevant to your reality.’” Today, the MBTI has become one of the most popular, well-researched, and well-known personality assessments of our time—but it does receive its fair share of criticism (which we’ll get into later on). You can take the assessment online, though Hackston says you can also work with someone who’s trained in the MBTI, to find out your type and how to work with it. All of the questions in the assessment, Nardi adds, will relate to the four preference categories. Here’s a breakdown of each of those categories: She adds that most of us are likely a mix of both (aka an “ambivert”), though “your type depends on which one you tend to gravitate toward more.” His ideas were then picked up by Katharine Cook Briggs and, later on, her daughter Isabel Briggs Myers. “Isabel developed the first version of the MBTI, so that’s why it’s called the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator—because it was Isabel and her mother who were ultimately behind it,” Hackston explains. From there, the first commercial version of the MBTI came out in 1977, he says. And since then, a lot of research has been done to modify and improve it. The most recent development of what Hackston calls the “new global version” of the MBTI is just over a few years old, having been updated in 2018. It’s also worth noting that some of the research in support of the MBTI’s validity is funded by companies that sell the assessment and follow-up materials, calling conflicts of interest into question. But some studies have indeed found the MBTI to be a good measure of personality. In a 2002 study1 published in the journal Educational and Psychological Measurement, the authors write, “The MBTI and its scales yielded scores with strong internal consistency and test-retest reliability estimates.” The MBTI also has research-backed implications for romantic compatibility. One study2, for example, found that if two people are the same in sensing/judging (ESTJ, ESFJ, ISTJ, ISFJ) or intuition/feeling (ENFP, INFP, ENFJ, INFJ), there’s a greater than 70% chance of being compatible in a relationship. Importantly, even proponents of the MBTI admit that your type won’t determine everything about you. “Research says that about half of what you do and who you are is ultimately about your type. It’ll also be affected by your upbringing, your environment, all sorts of things,” Hackston notes. In a 1993 paper titled “Measuring the MBTI and Coming Up Short,” David Pittenger, Ph.D., a professor of psychology at Marshall University, reviews the research on the Myers-Briggs test and raises questions about its underlying concepts. “The MBTI reminds us of the obvious truth that all people are not alike, but then claims that every person can be fit neatly into one of 16 boxes,” he writes. “I believe that MBTI attempts to force the complexities of human personality into an artificial and limiting classification scheme. The focus on the ’typing’ of people reduces the attention paid to the unique qualities and potential of each individual.” To that, Hackston and Nardi explain that these types are about preferences, and your type doesn’t suggest you can’t move outside your own preferences. Nardi says you can think of it like whether you’re left or right-handed. “If I’m right-handed, that doesn’t mean I don’t use my left hand, or I don’t use my hands together,” he explains. Hackston notes the results are meant to be more of a “springboard” for understanding your preferences so you can recognize your own patterns and actively choose to “go against your type” when situations call for it. Some experts also do not respect the work of Carl Jung, Katharine Cook Briggs, or Isabel Briggs Myers. Jung, for one thing, has received plenty of criticism, given how much of his theories were based on his own dreams and ideas as opposed to scientific fact. Cook Briggs and Briggs Myers were also not trained psychologists or mental health professionals, though Nardi points out that this particular criticism is “actually incredibly sexist because, at the time, it was very difficult for women to become psychologists or even get into college.” Another criticism of the MBTI is using it to assess or predict performance in the workplace, which Hackston, Hallett, and Nardi all agree is not what this assessment is intended for. “It’s not about performance—it’s about preference. No personality assessment should be used for hiring, and in some states, it’s actually illegal to use it that way,” Nardi notes. And then you have your more abstract, less scientifically sound ways to understand your personality, such as astrology or human design, which have no real evidence to support them but nevertheless receive plenty of attention from people curious to understand themselves. And those two, of course, are not based on a self-reported questionnaire but on your birth date, birth time, and birth location. The key to understanding the MBTI in relation to other personality assessments, according to Hackston, is to recognize that the MBTI is simply intended to work with the four preference categories and give you one of the 16 types. He adds that comparing these different tests is like comparing a screwdriver to a hammer; they’re not meant for the same purpose. Each type comes with its set of strengths and weaknesses, so identifying yours can help you make decisions. “Knowing your type is like having a shorthand description of common challenges or areas of success. Often, people find this to be more affirming than a source of ’new’ information about themselves,” Hallett adds. And as Nardi notes, when you understand someone else’s type, you also understand why they do the things they do, so in times of conflict, you can meet them halfway. That’s right—“We actually have choice about how we can express ourselves, and a lot of it is about perspective shifting,” Nardi explains. “So, once I know what my type is and learn that people are different types, that gives us room to not be thinking, ‘My way is the best way,’” for example. Like any personality assessment, the key to understanding and working with your MBTI type lies not in putting yourself in a box but in developing a greater understanding of your patterns and making changes where you see fit. As Nardi puts it, “We are not a type; we have a type—and we have choices.”