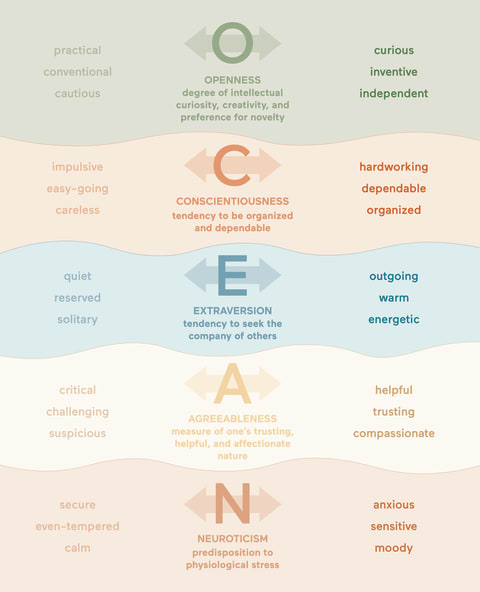

Many psychologists consider the so-called Big Five personality traits the most reputable. This model states that personality comes down to five core factors: openness, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. “Personality is defined as someone’s usual patterns of behaviors, feelings, and thoughts. While these usual patterns are complex, there are some personality traits that organize our understanding of someone’s personality,” explains licensed clinical psychologist Ernesto Lira de la Rosa, Ph.D., of the Hope for Depression Research Foundation. That’s where personality frameworks like the Big Five, also known as the Five Factor model, come in. According to the Big Five theory of personality, all human personalities are composed of these five core personality dimensions, and any individual’s personality boils down to where they fall on each of these five scales. Although not without its criticisms, decades of research have validated this theory. As with any personality test, there is controversy over the model itself and how it is best applied, says psychotherapist Lee Phillips, Ed.D., LCSW, CST. That said, today the Big Five personality traits are widely accepted as an accurate way of understanding human personality among most psychologists in the United States and in the broader Western world, supported by ample research. And as one 2020 paper in The Wiley Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences notes, “The five factors have provided a framework for understanding psychopathology. Neuroscience has identified neural correlates of the five factors, and cross-cultural research has underscored how people across the globe are both similar and different.” Below is a breakdown of each of the Big Five personality traits: According to Lira de la Rosa, “People who score high on openness tend to enjoy trying new things, playing with complex ideas, and considering alternative perspectives. Those who score lower on openness may dislike change, trying new things, and dislike abstract concepts.” According to Lira de la Rosa, those who score high on conscientiousness may spend more time preparing for things. They pay close attention to detail and enjoy a set schedule. “However, those who score low on conscientiousness may dislike structure and schedules and may procrastinate on important tasks,” he says. Introverts don’t necessarily dislike social gatherings; however, they may get fatigued by them and require time alone to regain their energy. “Those who score high may feel empathy and concern for others, enjoy helping others and contributing to their happiness. They love to assist those who are in need. In contrast, those who score low on agreeableness may take little interest in others, insult or belittle others, and have little interest in other people’s problems,” says Lira de la Rosa. Phillips explains that “high scores indicate the person is anxious, irritable, they are capable of anger outbursts, and they can have dramatic shifts in their mood. Low scores indicate the person does not worry as much, they are calm and emotionally stable, and they rarely feel sad or depressed.” “These traits are important because they are useful in understanding our social interactions with others. They are also helpful in increasing our self-awareness and how our personality traits may impact how others perceive or experience us,” Lira de la Rosa tells mbg. The Big Five model has evolved with time, research, and technology. These days, it’s regularly applied in social, academic, and professional contexts. The Big Five personality traits are foundational to personality tests that have become popular in dating, family, and work. Drawing from the same scientific research that generated the Big Five, the Myers-Briggs (MBTI), Likability Test, and the Difficult Person Test are related personality assessments meant to understand how an individual’s traits manifest in relationships with others. Tools and tests like these are often used to build relationships, romantic or professional. In the field of organizational behavior, tests based on the Big Five personality traits are often used in employee assessment tests, offering rubrics to understand employee character and to guide teams composed of diverse individuals. Gordon Allport, an American psychologist sometimes described as a founder of the field of personality psychology, published in the 1920s about what he termed “cardinal traits,” core characteristics thought to define a person’s personality. His research developed a lexicon of over 4,500 vocabulary words to describe personality traits. Then in 1949, through a study of clinical trainees, Fiske attempted to find consistent structural factors of personalities1. He identified a core group of four similar factors, with three distinct levels of behavioral ratings. As the field of psychology developed, personality research became more refined and competing, but related frameworks developed—some with as many as 16 factors and others with as few as four. But, somehow the number five kept coming up. Robert Costa and Paul McCrae developed the so-called Five Factor Model in 1987, and Lewis Goldberg developed the “Big Five Model” in 1993, both using the same core personality factors: openness, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. Since then, these Big Five personality traits have been studied and validated time and time again by many researchers over decades. Some of the most interesting recent research suggests that biological and environmental factors play a role in personality development. For example, a 2015 study of the personalities of twins2 suggests that both nature and nurture affect the development of each of the Big Five personality traits. In that study, 127 pairs of fraternal twins and 123 pairs of identical twins were put to the Big Five test. The findings showed the heritability of openness and neuroticism, and subsequent research has been done to further explore the genetic basis for some of the other traits. There is also some valid criticism of the Big Five personality traits. “In particular, most of the research on personality is done with people from western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic countries,” explains Lira de la Rosa. “As such, the Big Five personality traits may not capture personality traits across cultures.” He says that research shows that some of the Big Five personality traits are not observed as often in some other cultures. Phillips also adds that critics ask, “How can one test determine a person’s personality?” After all, personalities may shift over time. And it’s the mix of traits—not each one individually—that defines our personalities. So, tests like these—when not taken under the supervision of a trained professional—can sometimes be used to justify ill-conceived or overly simplified conclusions about people’s characters. “The average person can use personality traits to better understand themselves and how some of these traits impact their day-to-day functioning,” explains Lira de la Rosa. “It is important to note that these traits will not mean the same for each person, and it is the combination of these traits that informs our unique personalities.” Originally from New Jersey, she has lived in Spain, India, Mozambique, Angola, and South Africa. She speaks four languages (reads in three), but primarily publishes in English. Her writing placements range from popular trade magazines like Better Home & Gardens, Real Simple, and Whetstone to academic journals like Harvard’s Transition Magazine, the Centre for Feminist Foreign Policy, and the Oxford Monitor.